Controlling Nutrient Runoff Focus of Second Virtual Session of GLLC’s 2020 Meeting

In most years, on most days, nutrients from the agricultural operations of the Great Lakes region largely stay on the fields. But when heavy rains come, the runoff of phosphorus and other nutrients occurs, as they leave the fields, enter streams, and ultimately reach the lakes.

“The practices that are in place don’t work during those moments [of big storm events],” said Santina Wortman of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes National Program Office during a Sept. 21 meeting of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Legislative Caucus.

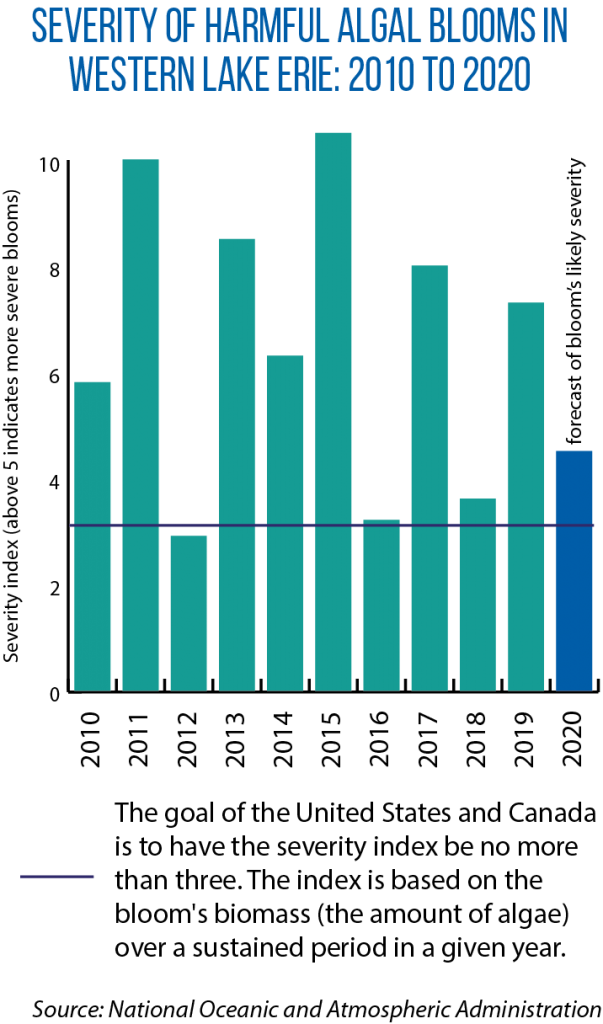

The result is a health and environmental problem that continues to vex the region’s policymakers, particularly those representing the western Lake Erie basin: how to get phosphorus loads below targeted levels in order to prevent harmful algal blooms.

That issue was the focus of the second of four virtual sessions being held as part of the GLLC’s 2020 Annual Meeting. Along with hearing from Wortman, lawmakers were briefed by Wisconsin Sen. André Jacque on the GLLC’s new model policies for reducing nutrient pollution. Sen. Jacque serves as chair of the GLLC Task Force on Nutrient Management, which developed the policies.

Wortman spoke to state and provincial legislators about the progress and status of Annex 4 of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, the binational commitment between the United States and Canada (last updated in 2012) to restore and protect the waters of the Great Lakes. Annex 4 outlines the two countries’ plans for reducing nutrient pollution.

The two nations have determined that a 40 percent reduction is needed in Lake Erie’s western and central basin, and the state governments of Michigan and Ohio as well as the province of Ontario have committed to that same level. Under that state-province Western Lake Erie Collaborative, the 40 percent reduction is supposed to be met by 2025.

But as Wortman noted in her presentation, progress has been slow, despite new investments and initiatives across the basin. “We haven’t seen any kind of downward trend yet in terms of the [harmful algal] blooms,” she said.

And since 2012, annual phosphorous loading has exceeded targeted levels every year but one — with that single exception being a very dry year that didn’t have the kind of big rain events that lead to nutrient runoff.

According to Wortman, nonpoint source pollution from agricultural operations account for much of the nutrient pollution in western Lake Erie (85 percent in the Maumee River watershed, for example).

To date, the policy response has centered on voluntary, incentive-based initiatives, such as conservation programs funded by the states or U.S. Farm Bill and “4R” projects that help farmers improve their management practices.

The states of Michigan and Minnesota offer voluntary certification programs for agricultural operations that meet certain water quality standards and implement state-approved conservation practices. In return for meeting these criteria, farmers receive recognition and regulatory certainty from the state.

Wisconsin offers grants to groups of agricultural producers that collaborate on new conservation initiatives in a single watershed of the state.

Most recently, Ohio legislators invested $172 million this biennium in a new H2Ohio Initiative, with one of the four main goals being a reduction in phosphorus runoff that comes from the commercial fertilizer and manure on farmland. The state Department of Agriculture is funding projects that change nutrient-management practices in the counties that make up the Maumee River watershed. State incentives will go to farmers that have been certified as having adopted a mix of nine “best practices” in nutrient management — for example, soil testing and the use of cover crops and edge-of-field buffers.

Recent initiatives have also targeted reductions in point-source pollution.

One notable success story, Wortman said, has been the results of facility and operational improvements at the Great Lakes Water Authority, which provides water and sewer services in the Detroit area.

“It has already achieved a 400-metric-ton reduction, which goes a long way toward Michigan’s [overall] 40 percent reduction goal,” she said, adding that, along with these new initiatives, other positive signs include an increased use of science and monitoring to help inform policymakers. But this research also shows that reducing harmful algal blooms and lowering phosphorus loads could take many years due to factors such as “legacy phosphorus” — the buildup of this nutrient from previous years’ applications.

“That is going to take some time to work through the system,” Wortman said. “And in any given year, you have a combination of what was applied this year and what was there from before.”

The GLLC made a reduction in nutrient pollution the focus of its 2019 Patricia Birkholz Institute for Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Policy. Funding for the institute and for the GLLC’s work on nutrient pollution is provided by the Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation.

At the Sept. 21 meeting, the Caucus also voted on the focus for the next Birkholz Institute, which will take place in late 2021. Members chose to concentrate on helping communities to become climate resilient.

The meeting was recorded and the slide deck is included in the virtual briefing book for the 2020 Virtual Meetings. The GLLC will continue its Virtual Meeting with two more sessions on October 2 and October 9, both starting at 9 am CDT/10 am EDT. Visit the meeting webpage to learn more about the remaining sessions and to register.